Spotlight: Why iRobot’s Robots Are Cleaning Up

May 14, 2018A common asset possessed by every highly innovative company in the Knowledge Leaders Indexes is a rich store of intangible capital. Such reservoirs of knowledge take the form of trademarks, brands, software, even manufacturing processes, and there is only one way to amass them: over time. Deep stores of knowledge accumulate when companies make the decision, year after year, to invest in innovation.

iRobot, which has sold 20 million Roomba robot vacuums worldwide, illustrates how a company can systematically make choices that position it to lead its industry, fend off competition, and even build in the tendency to deliver excess returns in the stock market (see The Knowledge Effect: Excess Returns of Highly Innovative Companies).

In fact, iRobot’s founders never intended to make vacuum cleaners at all. When the three MIT grads launched the firm in 1990, they wanted to build robots. The firm’s first models set out to mimic the movements of insects to explore Mars and scour earth’s oceans for undetonated mines.

Since there was barely a sliver of a robot industry at the time, the young firm found itself in the position of not only building the robots they dreamed of selling, but also creating a framework for the fledgling robot industry. With this came with the responsibility to create expectations, institutions and social norms that would define an ecosystem for products that existed only in their imaginations. Not to mention the task of building trust in the face of a fictional Hollywood-spun history depicting machines that looked like humans and talked like humans and could be deployed for good or evil – far from the actual reality of robot technology.

In 1998, iRobot got its first big break, a major DARPA contract to build its “Packbot” tactical mobile robots for military reconnaissance. When the September 11 terrorist attacks hit, iRobot pulled the fledgling PackBot out of the lab and sent it to assist search and rescue teams in areas deemed too risky for humans. As the war in Afghanistan took off, PackBot was deployed to the Middle East to help explore complicated networks of underground tunnels. There, PackBot also earned the affection of troops for its bomb disposal work with IEDs or improvised explosive devices, saving lives of operators who could now “send the robot in first.” In 2002, in an experimental project, iRobot sent a robot into a narrow shaft in Egypt’s Great Pyramid to explore a previously inaccessible chamber.

It was through these missions that iRobot struck on and began the multi-decade development of the signature technology that sets it apart from competitors. Reconnaissance tasks require a complex process of navigation and mapping. By trial and error, engineers developed an integrated system of software, hardware and electronics that enables its robots to complete complex tasks.

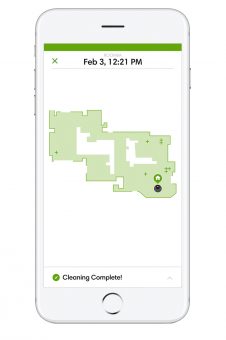

As a result, the firm’s newer generation Roomba robot vacuums use an adaptive technology with over 40 robotic behaviors that allow Roomba to make more than 60 decisions per second to ensure they clean every section of the room and make multiple passes over every area. Optical and acoustic sensors find the dirtiest parts of the floor and decide which cleaning pattern to use. New generations of Roomba will even send you a map of your floor and exactly where it was cleaned.

According to the firm’s 10-K, as of the end of 2017, iRobot held 403 U.S. patents, more than 650 foreign patents, and had more than 450 more patent applications pending worldwide. It’s this sort of innovation heritage that separates the Knowledge Leaders from the Followers.

So how did iRobot go from building military robots to single-handedly creating the robot home cleaning category in 2002? As the story goes, in his first decade in the industry, the firm’s founder and CEO was asked everywhere he went, “when are you going to make a robot to clean my house?”

The joke gained traction after engineers got serious about reducing costs to reach a consumer price point, and the MIT roboticist who never imagined himself a vacuum cleaner salesman, soon found himself carrying a Styrofoam coffee cup full of dirt in his suit jacket pocket to meetings – to demonstrate that a robot really could clean.

Indeed cultural baggage created a unique set tailwinds and headwinds for iRobot’s first consumer robot. Some had read Isaac Asimov as children and still believed that when the robots arrived, it was only a matter it time before they took over. Others couldn’t explain their opposition to robots, like the writer who recommended against Roomba in a major national newspaper review because they felt the floor could only really be clean if they personally pushed the vacuum.

Fortunately for Roomba, the tailwinds were similarly charged. The waiting community of early adopters and gadget enthusiasts that embraced Roomba’s launch in 2002 would have bought the new robot no matter what it did. Next came the personification – Roombas nicknamed and anthropomorphized with googly eyes, custom R2-D2 skins, and mounted with Yoda dolls. Roomba races. Roomba Frogger across the highway. Videos of babies, puppies and kittens riding, chasing, playing with and/or sleeping amongst working Roombas. People crying as they unwrapped the gift paper on a new Roomba. School children giving presentations on how Roomba works. All of this has engendered a unique community of brand advocates for the iRobot and created another layer of intangible assets for the firm.

Sixteen years after Roomba’s launch, robots now comprise one fifth of the global vacuum market. Having spun off its military division, today iRobot’s singular mission is to develop smarter and more productive ways to clean. Depending on the model, Roomba robot vacuums cost $299-899. The firm’s Braava mopping robots cost $199-299. The Mirra pool cleaning robot, offered through a partnership and with Aquatron, and can be found at Amazon, Wal-Mart or Best Buy for $899-999. iRobot names its top priorities as expanding Roomba adoption worldwide, developing its floor mopping business and developing new connected home robots.

In the future, it envisions a Smart Home where robots work together to complete tasks. Already it has integrated Wi-Fi into its cleaning robots, forged a new relationship so your Roomba can “talk” to Amazon’s Alexa, and launched an iPhone app so you can start your Roomba while you’re at work. It will send you a post-mission cleaning map when the job is done.

iRobot protects these assets and takes seriously its role as an evangelist for the robot category. At the firm’s Bedford, Mass., headquarters, enthusiasts can visit its robot museum. The company hosts tours and demonstrations for schools and sponsors pro-STEM, engineering and robotics initiatives and contests for students, most recently National Robot Week, Women in Tech and Girls Who Code. This small-cap firm employs about 920 people.