Spotlight Equinor: How Energy’s Harsh Storms Led to a Greener, Smarter Future

October 17, 2018At the trough of the oil crisis in 2015, Equinor’s management was scrambling to prepare the company for an unknown future. Management believed that while the oil and gas industry would eventually recover, the industry would never be the same. The team decided to use the setback as an opportunity to reset the company. To embrace change. Then in December of 2015 another blow for oil and gas: nearly 200 countries committed to work together to mitigate global warming in the Paris Accord, pressuring an energy industry already in transition to drastically reduce carbon emissions.

Norway’s state oil company, founded in 1972 and known as Statoil until this year, could have deployed a business-as-usual strategy. After all, the government of Norway owns 67% of the company. But stagnation is not in this Knowledge Leader’s DNA.

One can almost predict what the company did next simply by looking at our intangible-adjusted data. While Equinor doesn’t make the supermajors list of the top six oil and gas companies in the world, nor is it present on the list of the top 10 oil and gas companies by revenue, Equinor has the second highest R&D as a percent of sales of any developed market integrated oil and gas company, behind Total SA. As we know from our work studying the most innovative companies in the world, firms with a commitment to innovation develop rich stores of intangible capital that pay off over time.

So while Equinor was quietly investing in its future, it made two public commitments with the intention of leading a transformation in the energy industry. First, Equinor announced a plan to become the world’s most carbon efficient producer of oil and gas. It committed to allocate 25% of its research to new energy by 2020. Second, the firm launched a digital roadmap, committing to deploy digital technology toward increasing productivity and reducing its carbon footprint.

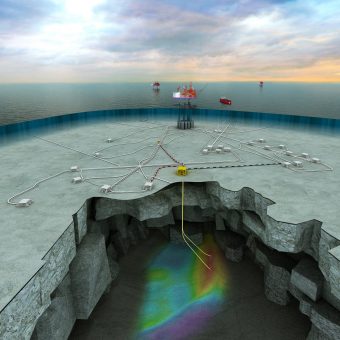

This included the introduction of machine learning and artificial intelligence to generate cloud-based analysis of the 26 petabytes of geological data (that’s about 50 times the size of the US gene database) gathered from its sensors on the bottom of the ocean floor. It set up a Digital Centre of Excellence, applying data analytics and AI to its own R&D efforts as well as joint projects with academia, outside researchers and suppliers. It teamed up with a group of energy majors, banks and trading houses to use blockchain technology to explore creating a new, cheaper and safer platform for secure, digital and authenticated transfers.

Subsea factory, credit: Equinor

“Innovation and technology will transform us,” Equinor’s Director of Innovation Anders Hegna Haerland said. “Society around us, and the energy industry along with it, have never been changing as rapidly as they are now. This means that the rate of change in our company also has to increase.”

But results were not immediate. In 2015, Equinor suffered accidents – an oil spill, rig injuries, evacuations due to storms and gas leaks. In 2016, the company’s luck was even worse. One of the firm’s helicopters crashed on route to a rig in the ocean, killing 13 workers. Fires, injuries and leaks plagued its operations. An employee was investigated for corruption and ultimately cleared of wrongdoing. Net operating income was close to zero for 2016.

Equinor remained focused on its vision, even as pressure from the supermajors was building, for they too were scrambling to catch up with technology advances. At stake, reported the WSJ, “is $300 billion – the potential savings from big oil companies’ digital push – according to an analysis by JP Morgan. The bank estimates that efforts to harness data and automate drilling could slash the sector’s $1 trillion in annual global capital expenditures roughly a third by 2021.”

Credit: Equinor

Finally, in 2017 came a turning point. The firm led the industry in launching the world’s first automated oil rig in the North Sea. The unmanned well uses digital sensors and fiber-optic cables to monitor every function of the rig remotely in real time by a team onshore and only needs to be visited once or twice a year. By this time Equinor was deploying other breakthrough automated technologies in the ocean too. Fully half of Equinor’s production now came from subsea wells, built Lego-style with modular pieces that snap together and rest at the bottom of the ocean with no visible rig on the surface. A generation of snake robots called “Eelume” now lived underwater, performing small tasks underwater like turning on and off valves and filming pipelines for faults. Autonomous free-swimming drones called “Hugins” were mapping the seabed, taking measurements and recording sound. Two Equinor employees who studied cybernetics at Norwegian University of Science and Technology had developed a cleaning robot that was now at work on Equinor’s rigs cleaning and inspecting tube heater exchangers while operations continued, increasing productivity and eliminating the use of chemicals by using only high-pressure water to clean.

Eelume snake robot lives permanently under water, credit: Equinor

Hugin autonomous ocean mapping drone, credit: Equinor

Also by 2017, Equinor was now two years ahead of schedule on its commitment to reduce annual CO2 emissions by 1.2M tons by 2020, the equivalent of the total emissions from some 600,000 private cars annually, or almost every fourth car on Norwegian roads. By now Equinor also had reduced carbon intensity to about 10kg CO2 per barrel compared to the industry average of 17kg CO2 per barrel. The firm also began production at its flagship new energy invention: the world’s first floating wind farm off the coast of Scotland. The Hywind Park’s floating wind turbines are located in deep water where as much as 80% of the total potential for offshore wind power is believed to be and Equinor is uniquely positioned to reach.

Floating wind farm, credit: Equinor

Today, the results of Equinor’s R&D efforts are stacking up. Last year’s net operating income ended positive USD $13.8 billion, up from close to zero in 2016. A major seller of crude oil, Equinor is now the second-largest supplier of natural gas to the European market. Serious incidents are down. The company now operates three wind farms off the coast of the UK with large-scale projects in the works offshore of the UK, Germany and the US and new investments in solar projects in Brazil and Argentina. In May of this year, the firm changed its name from Statoil to Equinor. The new name combines its Norwegian origin with corporate values of equality and equilibrium. Shedding the word “oil” from its name aimed to broaden the firm’s appeal to young people, who tend to be concerned about climate change and who began to show less interest in working for oil firms and more interest in working in renewable energy after oil prices crashed in 2014.

While Equinor remains No. 2 on the list of oil and gas companies investing in R&D, it has plenty of company chasing innovation. This summer, The Wall Street Journal reported on Big Oil’s digital transformation, describing the shift from the view of a BP employee named Ian Gallagher. “He started in a Colorado oil field nine years ago for BP, climbing radio towers for repairs. He had attended a few semesters of college but didn’t graduate. In 2014, he saw the company starting to change around him and decided to teach himself Python and other common programming languages. Now, he works out of a BP office in Durango, Colo., designing wireless monitoring prototypes for BP compressors. ‘The way I’ve dealt with it is to learn as much as I can and adapt.’ Ian Gallagher said.”

Equinor has 20,245 employees worldwide.

As of 9/30/18, Equinor was owned and Total SA and BP were not owned in the Knowledge Leaders Strategy.